19 June 2024

Resumen

Las normas de producción ecológica implican que no se pueden utilizar productos sintetizados químicamente para el control de plagas. Sin embargo, la coexistencia con la agricultura convencional en la misma área puede dar lugar a cierta presencia de pesticidas.

Una de las fuentes de estos residuos puede ser el compost, procesado a partir de restos de cultivos convencionales, que está permitido como fertilizante orgánico en la agricultura ecológica.

En este estudio, se investigó la posible transmisión de residuos de pesticidas de un compost disponible comercialmente a plantas de pepino.

Las plantas de pepino se cultivaron en contenedores, ya sea en un sustrato básico con compost añadido, o en el mismo sustrato sin añadir compost (control).

De los 13 residuos de pesticidas diferentes que estaban presentes en el compost, se detectaron 4 ingredientes activos mediante un análisis de residuos múltiples en muestras de hojas de las plantas cultivadas con compost, y no en las plantas de control. Ninguno de estos residuos se detectó en muestras de frutos.

Se concluye que el compost derivado de la agricultura convencional puede ser una fuente de contaminación por pesticidas de los cultivos orgánicos, como se detecta en el análisis de residuos de la masa foliar.

En algunos casos, esto puede llevar a conclusiones falsas sobre la posible violación de las normas de producción ecológica por parte de los productores.

1- Introducción

En el proceso de compostaje de residuos agrícolas se degradan la mayoría de los contaminantes orgánicos, como los pesticidas. Kupper et al. (2008) encontraron que alrededor de dos tercios de todos los pesticidas detectados en los materiales de entrada mostraron tasas de disipación superiores al 50 % durante el compostaje. Aunque muchos ingredientes activos ya no se detectaron después de 112 días, la concentración de residuos de otros pesticidas apenas se redujo, como se observó particularmente en los fungicidas pertenecientes al grupo de los triazoles.

Hallazgos similares fueron presentados por García Rández (2020), quien analizó 323 ingredientes activos potencialmente detectables en 25 pilas con residuos de diferentes tipos de cultivos, antes y después del compostaje. En las mezclas iniciales se detectaron 42 ingredientes activos, es decir, 28 fungicidas, 11 insecticidas y 3 herbicidas. Después del compostaje, esto se redujo a un total de 33 ingredientes activos: 24 fungicidas y 9 insecticidas.

La alta diversidad y actividad microbiana durante el compostaje, debido a la abundancia de sustratos en las materias primas, promueve la degradación de compuestos orgánicos xenobióticos, como pesticidas, hidrocarburos aromáticos policíclicos (HAP) y bifenilos policlorados (PCB) (Barker et al., 2002).

La contaminación de los cultivos por pesticidas es especialmente importante para la agricultura ecológica, donde el uso de compost, también derivado de la agricultura convencional, está permitido y es una práctica común. Las normas de producción ecológica implican que no se pueden utilizar productos sintetizados químicamente para el control de plagas o la fertilización.

Sin embargo, la coexistencia y proximidad de sistemas agrícolas convencionales en la misma zona puede dar lugar a cierta presencia de pesticidas que no se han utilizado en el cultivo (Bernasconi et al., 2021; Schleiffer y Speiser, 2022). Pequeñas cantidades de residuos pueden entrar en los cultivos ecológicos, por ejemplo, directamente por ‘deriva’, cuando los cultivos convencionales vecinos son tratados con productos fitosanitarios, o indirectamente a través de residuos presentes en productos de entrada, como fertilizantes orgánicos.

En la mayoría de los suelos agrícolas, incluidos los suelos de explotaciones ecológicas, existe una presencia persistente de pesticidas debido a prácticas agrícolas en el pasado (Silva et al., 2019; Geissen et al., 2021; Riedo et al., 2021; Junta de Andalucía, 2022).

En muchos casos, estos residuos permanecen después de varios años de horticultura ecológica. Esto se ha demostrado para algunos pesticidas antiguos extremadamente persistentes, cuyo uso ha cesado hace más de 3 décadas, como el DDT (Malusá et al., 2020), la dieldrina (Colin et al., 2022) o el lindano (Coexphal, informe no publicado), pero también para productos que todavía están en el mercado y se usan comúnmente.

Ejemplos de estos últimos son algunos de los fungicidas del grupo de los triazoles, como flutriafol con un DT50 (tiempo de degradación al 50 % de la concentración) en el suelo de más de 3 años (PPDB, 2023), pero también para otros productos clasificados como "persistentes".

La producción ecológica reduce la presencia de pesticidas en los suelos agrícolas entre un 70 % y un 90 % en comparación con la agricultura convencional, según un estudio realizado por Geissen et al. (2021) con 340 muestras de suelo de tres países europeos (Portugal, Países Bajos y España).

Además, se detectaron mezclas de hasta 16 residuos por muestra, en el 70 % de los suelos convencionales, mientras que solo se encontraron un máximo de cinco pesticidas diferentes en los suelos ecológicos.

Hasta ahora, está poco documentado cómo los residuos presentes en el compost pueden ser absorbidos por los cultivos. Este fue el tema del presente estudio de caso, en el que un compost disponible comercialmente, procedente de la horticultura convencional, se mezcló con un sustrato básico y se monitoreó la presencia de residuos de pesticidas en plantas de pepino.

2- Material y métodos

Las plantas de pepino (Cucumis sativa, var. Litoral®) se cultivaron en un invernadero experimental de la Estación Experimental Cajamar 'Las Palmerillas', Almería (España); los análisis de plaguicidas fueron realizados por Labcolor, laboratorio de la Asociación de Empresas Productoras de Hortícolas de Almería (Coexphal).

El experimento se repitió durante tres ciclos de plantación diferentes, con las siguientes fechas de plantación: 7 de octubre de 2021; 7 de marzo de 2022 y 14 de octubre de 2022

2.1.- Cultivo

A los 30 días de sembrar las semillas de pepino en bandejas de germinación, las plántulas se trasplantaron a macetas de 6 litros, llenas únicamente con el sustrato básico (control) o el sustrato al que se le añadió 60 g de compost en el primer y tercer ensayo, y 120 g en el segundo ensayo.

Se colocaron 6 plantas por repetición con tres repeticiones por tratamiento, en un invernadero experimental sin calefacción de 630 m2 (Figura 2), donde se manejaron de acuerdo con las prácticas hortícolas habituales.

Durante los dos primeros ciclos de las plantas, el sustrato básico consistió en una tierra homogeneizada que se tomó de una parte de una parcela que pertenece a la estación experimental, donde no se habían realizado tratamientos con pesticidas durante varios años.

En la tercera repetición, se utilizó fibra de coco comercialmente disponible (Fico®) como sustrato básico.

El compost se obtuvo de una planta local de gestión de residuos en Almería, que procesa residuos vegetales, principalmente de la industria de invernaderos de la zona. El compost estuvo, almacenado al aire libre en dicho centro y dispuesto en forma de pila, se utilizó para las tres repeticiones del ensayo.

2.2.- Tratamiento con pesticidas

Los cultivos se manejaron según las normas de Manejo Integrado de Plagas. Esto implica el uso de agentes de control macrobiológico contra plagas de insectos y ácaros y el uso de plaguicidas selectivos contra plagas y enfermedades adicionales. Los tratamientos se realizaron con plaguicidas que no fueron detectados en el análisis inicial de compost o suelo. Los productos utilizados fueron: Piretro natural; Cimoxanilo, Sulfoxaflor, Ciazofamida, Famoxadona y Metrafenona.

2.3.- Análisis multirresiduos

Antes de la plantación, se realizaron análisis multirresiduos (mediante cromatografía de gases y de líquidos) en los sustratos básicos y en el compost.

El compost se analizó dos veces: una antes del inicio del primer ensayo y otra una vez finalizado el tercer ensayo, es decir, 19 meses después del primer análisis.

De cada cultivo, se analizaron muestras de hojas y frutos en dos ocasiones. Las primeras muestras se tomaron alrededor de la primera cosecha y las segundas muestras aproximadamente un mes después. En los dos primeros ensayos, se tomaron 3 hojas de cada planta, del nivel superior, medio e inferior.

En el tercer ensayo, solo se tomaron hojas jóvenes, es decir, las primeras hojas completamente desarrolladas debajo de los puntos de crecimiento.

De todas las hojas, se cortó un fragmento que se homogeneizó y procesó para su análisis mediante cromatografía de gases y de líquidos. En todos los casos, el nivel de detección de los residuos se fijó en 0,01 ppm. Los análisis fueron realizados por el laboratorio de Coexphal (‘Labcolor’), La Mojonera, Almería.

3- Resultados

3.1- Residuos de pesticidas en el sustrato y compost

A pesar de haber elegido sustrato base una tierra procedente de una zona de la Estación Experimental en la que no se habían realizado tratamientos en los últimos años, se detectaron cuatro principios activos en este material.

Dos de ellos (Flutriafol y Fludioxonil) se encontraron también en el compost, donde se encontraban en concentraciones mucho más elevadas.

Los otros dos, no se detectaron en el compost, Tiabenazol y Lufenurón, son productos (muy) persistentes que no tienen registro para su uso en horticultura.

La Tabla 1 muestra los resultados del análisis de residuos del compost, así como de la tierra que se utilizó en las dos primeras repeticiones. No se detectaron residuos en la fibra de coco que se utilizó como sustrato básico en el tercer ensayo.

En el compost se detectaron trece principios activos en el primer análisis, al inicio del ensayo (Tabla 1).

En el segundo análisis del mismo compost, realizado tras finalizar el último ensayo, es decir, más de un año y medio después, había desaparecido un principio activo (Pyriproxyfen); dos se detectaron en concentraciones reducidas; uno de ellos se mantuvo igual y nueve plaguicidas mostraron concentraciones aumentadas. Este aumento probablemente se deba a la degradación (en peso y volumen) del propio compost, que no fue cuantificada.

Los principios activos encontrados en el compost son plaguicidas de uso frecuente en horticultura en Almería y pertenecen a los plaguicidas más frecuentemente detectados en abonos orgánicos por el laboratorio Coexphal (Labcolor, datos no publicados). Por tanto, el compost utilizado puede considerarse representativo de la zona.

3.2- Residuos de pesticidas en hojas

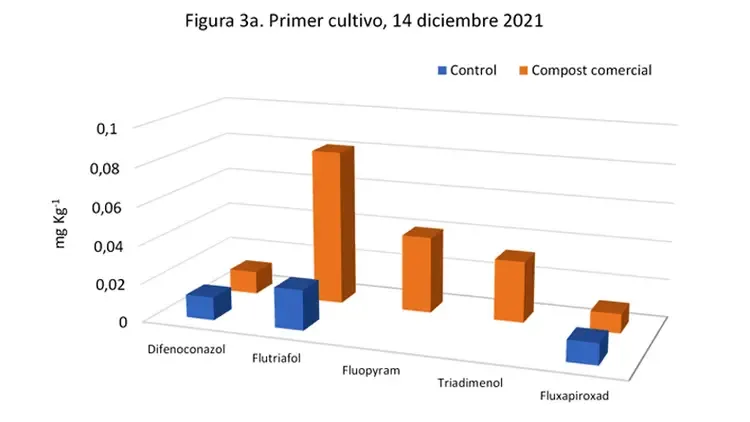

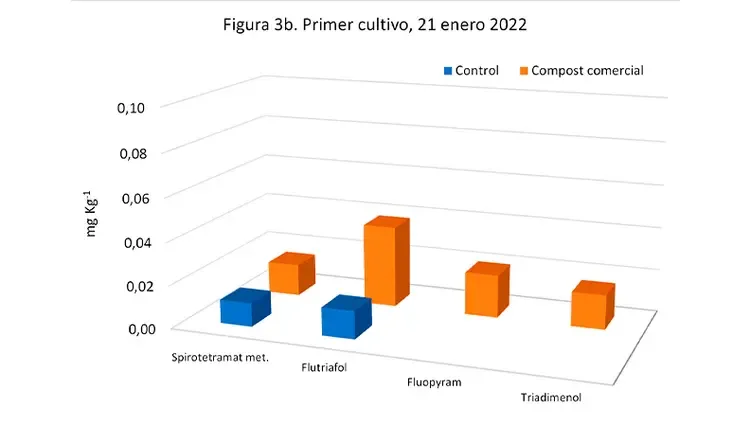

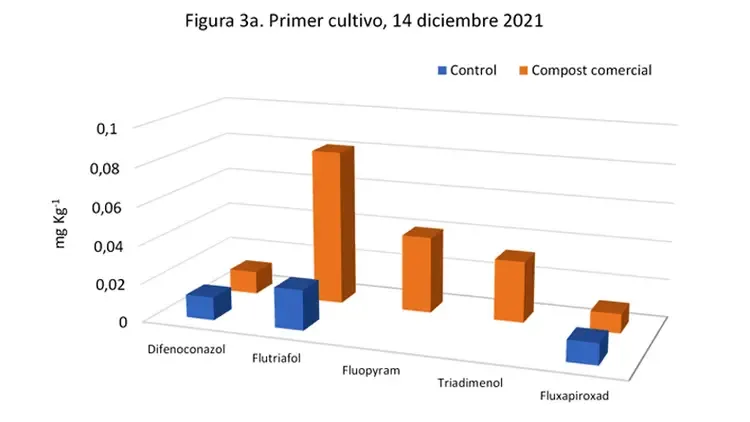

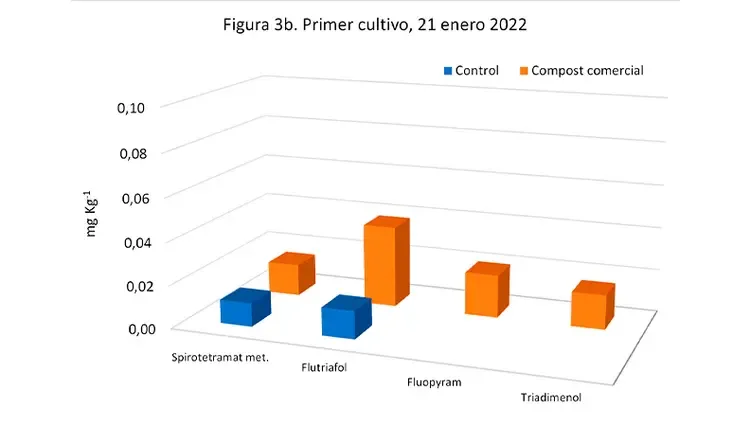

No se consideraron los plaguicidas aplicados al cultivo durante los ensayos. Los resultados del primer ensayo (Figura 3 a y b) muestran que se detectaron 5 plaguicidas en la primera muestra de hojas, alrededor de la primera cosecha (Figura 2a) y 4 en la segunda muestra (Figura 3b).

Dos productos, fluopyram y triadimenol, solo se encontraron en las plantas que se cultivaron en suelo con compost. flutriafol se detectó en ambos tratamientos, aunque la concentración fue aproximadamente cuatro veces mayor en las plantas que se cultivaron con compost.

Dos plaguicidas, difenoconazol y fluxapyroxad, se detectaron en concentraciones bajas similares en las plantas cultivadas con y sin compost en la primera muestra. En la segunda muestra, este fue el caso del espirotetramat.

Dado que fluxapyroxad y espirotetramat no se encontraron en el compost ni en el suelo (Tabla 1), ni se utilizaron para el control de plagas en este cultivo, estas detecciones probablemente sean el resultado de contaminaciones. Ambos productos se utilizaron en otros invernaderos de la estación experimental, por lo que la detección en este ensayo pudo haber sido causada por deriva o por restos de estos pesticidas en el equipo de pulverización.

El difenoconazol se detectó en el compost pero no en el suelo (Tabla 1), por lo que no está claro el origen de una baja concentración en las plantas control.

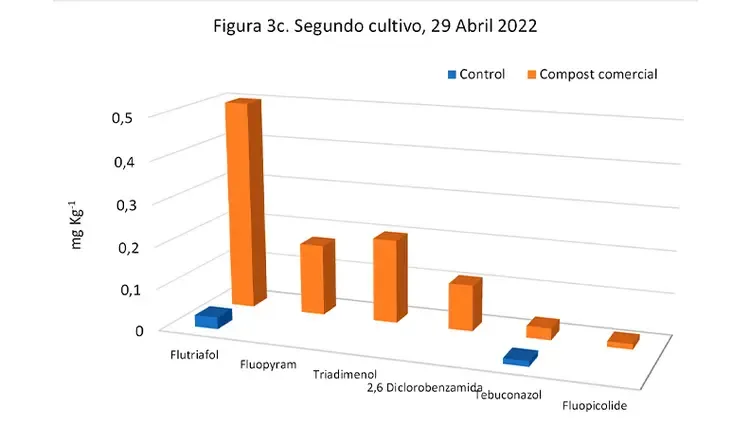

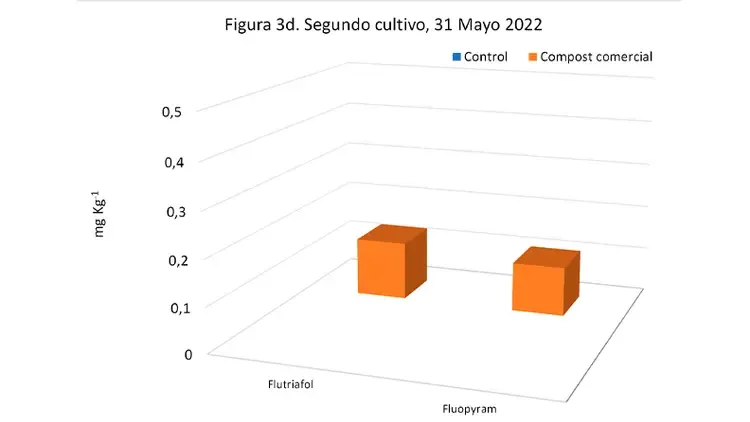

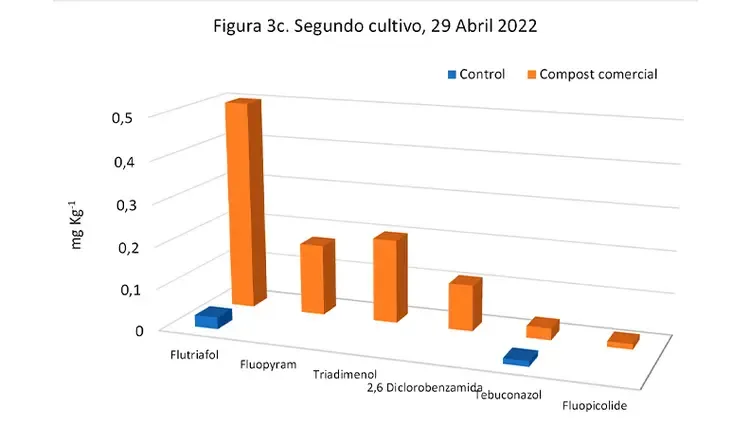

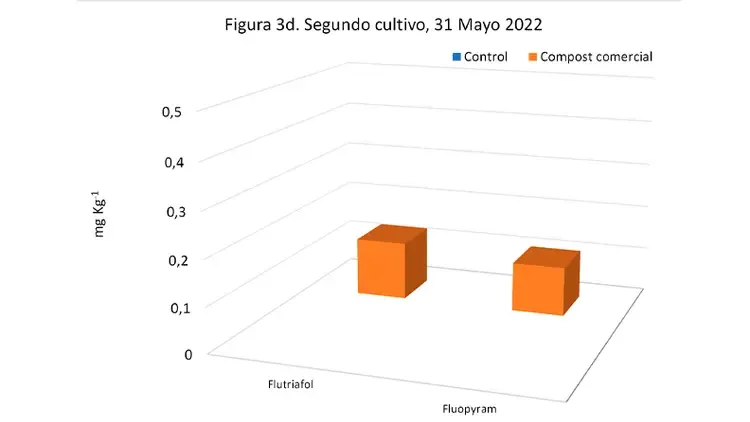

En el segundo ensayo, se detectaron cinco pesticidas que parecen estar relacionados con las concentraciones en compost y suelo. Fluopicolide, fluopyram y triadimenol solo se detectaron en las plantas cultivadas con compost, el flutriafol se encontró en una concentración relativamente alta en estas plantas pero también en una concentración baja en las plantas control (Figura c y d).

En la primera muestra, el tebuconazol estaba presente en ambos tratamientos, aunque en una concentración ligeramente superior en las plantas con compost. El origen de este pesticida en las plantas control no está claro, ya que no se detectó en el suelo.

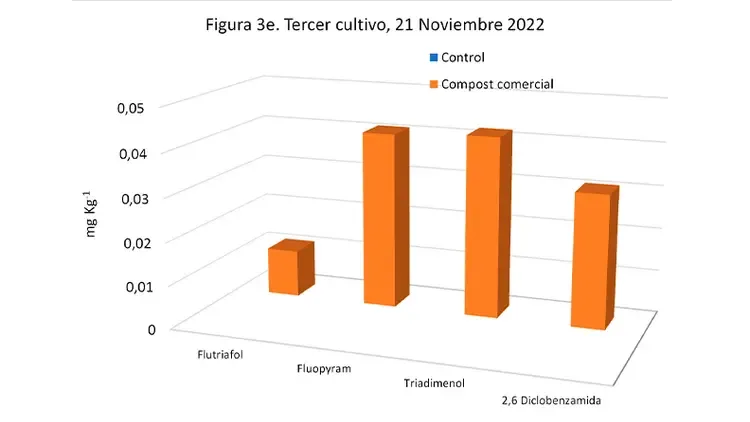

En el tercer ensayo, el sustrato básico utilizado fue fibra de coco, en el que no se encontraron residuos de pesticidas previamente.

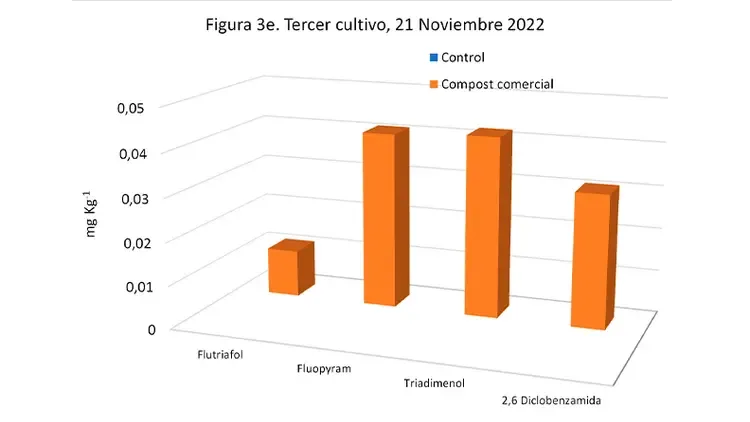

La primera muestra de este ensayo reveló residuos de cinco pesticidas, es decir, fluopicolide, fluopyram, flutriafol y triadimenol en las plantas cultivadas con compost y ningún residuo en las plantas de control (Figura 3e). Los cinco productos estaban presentes en el compost (Tabla 1). No se detectaron residuos en la segunda muestra en concentraciones superiores al límite de detección.

Figura 3.- Concentración de plaguicidas (mg Kg-1) detectados en muestras de hojas de pepino, provenientes de plantas que fueron cultivadas en sustrato con o sin compost.

- Límite de detección: 0,01 mg Kg-1; Margen de error en todos los casos: 50 %.

- No se detectaron residuos en las segundas muestras del tercer ensayo.

4- Discusión

Los análisis foliares de las materias activas de los tres ensayos se encontraron tres principios activos procedentes del compost: triadimenol, flutriafol (ambos fungicidas triazólicos) y fluopiram (un fungicida benzamida).

En el segundo y tercer ensayo, también se encontró fluopicolide (fungicida benzamida). Las concentraciones detectadas fueron siempre notablemente superiores en la primera muestra que en la segunda de cada ensayo.

Aunque no se encontró ninguno de estos compuestos en las muestras de fruta, se puede concluir que el compost ha sido una fuente importante de contaminación por pesticidas de las plantas de pepino cultivadas.

Los residuos que se encontraron en las muestras de hojas fueron notablemente superiores en el segundo ensayo, que en los otros dos ensayos, debido a la mayor cantidad de compost que se aplicó (120 g por maceta de 6 l frente a 60 g por maceta de 6 l).

En el tercer ensayo, el sustrato básico que se utilizó fue diferente a los sustratos básicos utilizados en los dos primeros ensayos, es decir, turba de coco en lugar de tierra. Las bajas concentraciones de pesticidas detectadas en las muestras de hojas del tercer ensayo pueden ser consecuencia de la interacción de los residuos químicos con las fibras orgánicas de la turba de coco.

El registro de los dos triazoles que no está autorizadas en España desde 2021, por lo que actualmente estos productos ya no se utilizan. Sin embargo, cuando se cultivaban los cultivos que finalmente se procesaban como compost, hasta 2021, estos productos todavía pertenecían a los pesticidas más utilizados, el fluopicolide y el fluopyram siguen estando registrados y son de uso común.

Se permite el uso de compost de origen convencional en agricultura ecológica, con el objetivo de valorizar el valor fitonutricional de los residuos orgánicos según los principios de la economía circular. Esto significa que, mientras se permitan los productos fitosanitarios persistentes en la agricultura convencional, se deben tolerar pequeñas concentraciones de pesticidas en los cultivos ecológicos.

Normalmente, como en los ensayos aquí presentados, estos productos solo se detectarán en muestras foliares, dado que las contaminaciones en el suelo pueden concentrarse en las hojas, pero no en los frutos. El análisis de residuos de muestras de hojas puede incluso dar una falsa indicación de que los productores pueden haber violado las reglas relativas al manejo ecológico de los cultivos.

5- Referencias

- Bernasconi, C,, Demetrio, P,M,, Alonso, L,L,, Mac Loughlin, T,M,, Cerdá, E,, Sarandón S,J,, Marinoa, D,J,, 2021, Evidence for soil pesticide contamination of an agroecological farm from a neighboring chemical-based production system, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 313: 107341. https://doi,org/10,1016/j,agee,2021,107341

- Colin, F,, Cohen, G,J,V,, Delerue, F,, Chéry, P,, Atteia, O,, 2022, Status of Dieldrin in vegetable growing soils across a peri-urban agricultural area according to an adapted sampling strategy, Environmental Pollution 295. 118666, https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2021,118666

- García Rández, A, 2020, Análisis de la presencia de plaguicidas en las mezclas iniciales y compost maduros de productores agroecológicos de la Comunidad Valenciana, El rol del compostaje en su eliminación, Escuela Politécnica Superior de Orihuela (Alicante, Spain), Master thesis, 99 pp, http://193,147,134,18/jspui/bitstream/11000/6700/1/TFM%20Garc%c3%ada%20R%c3%a1ndez%2c%20Ana,pdf

- Geissen, V,, Silva, V,, Huerta Lwanga, E,, Beriot, N,, Oostindië, K,, Bin, Z,, Pyne, E,, Busink, S,, Zomer, P,, Mol, H,, Ritsema, C,J,, 2021, Cocktails of pesticide residues in conventional and organic farming systems in Europe - Legacy of the past and turning point for the future, Environmental Pollution 278: 116827 https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2021,116827

- Junta de Andalucía, Servicio de Calidad, Promoción Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, Depto, Ecología, 2022, INFORME DE RESULTADOS DE LA TOMA DE MUESTRAS Y ANÁLISIS DE RESIDUOS PLAGUICIDAS EN LA PRODUCCIÓN ECOLÓGICA EN ANDALUCÍA EN 2021, Junta de Andalucía, 17 pp.

- Kupper, T,, Bucheli, T, D,, Brändli, R, C,, Ortelli, D,, & Edder, P, (2008), Dissipation of pesticides during composting and anaerobic digestion of source-separated organic waste at full-scale plants, Bioresource technology 99(17), 7988-7994.

- Malusá E, Tartanus M, Danelski W, Miszczak A, Szustakowska E, Kicińska J, Furmanczyk EM, 2020, Monitoring of DDT in Agricultural Soils under Organic Farming in Poland and the Risk of Crop Contamination, Environ, Manage, 66(5): 916-929, doi: 10,1007/s00267-020-01347-9, Epub 2020 Aug 19, PMID: 32815049; PMCID: PMC7591450.

- McKinnon, K,, Serikstad, G,L,, Eggen, T, 2014, Contaminants in manure – a problem for organic farming? In: RAHMANN G & AKSOY U (Eds,) Proceedings of the 4th ISOFAR Scientific Conference, ‘Building Organic Bridges’, at the Organic World Congress 2014, 13-15 Oct,, Istanbul, Turkey, p 903-904.

- PPDB, Pesticide Property Database, Univ, of Hertfordshire. https://sitem,herts,ac,uk/aeru/ppdb/en/atoz,htm

- Riedo, J,, Wettstein, F,E,, Rösch, A,, Herzog, C,, Banerjee, S,, Büchi, L,, Charles, R,, Wächter, D,, Martin-Laurant, F,, Bucheli, T,D,, Walder, F,, van der Heiden, G,A,, 2021, Widespread Occurrence of Pesticides in Organically Managed Agricultural Soils - the Ghost of a Conventional Agricultural Past? Environ, Sci, Technol, 55 (5): 2919–2928. https://doi,org/10,1021/acs,est,0c06405,

- Schleiffer, M,, Speiser, B,, 2022, Presence of pesticides in the environment, transition into organic food, and implications for quality assurance along the European organic food chain – A review, Environmental Pollution 313, 120116 https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2022,120116

- Silva, V,, Mol, H,G,J,, Zomer P,, Tienstra M,, Ritsema C,J,, Geissen V,, 2019, Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils – a hidden reality unfolded, Science of The Total Environment 653, pp 1532-1545. https://doi,org/10,1016/j,scitotenv,2018,10,441

Versión en Inglés del estudio

Pesticide residues originating from compost in cucumber plants. A case study.

Abstract

The organic production standards imply that no chemically synthesized products may be used for pest control. However, the coexistence with conventional farming in the same area may lead to certain presence of pesticides. One of the sources of these residues may be compost, processed from conventional crop rests, which is permitted as organic fertiliser in organic farming. In this study, possible transmission of pesticide residues from a commercially available compost into cucumber plants was investigated.

Cucumber plants were grown in containers, either in a basic substrate with compost added, or in the same substrate without adding compost (control). Out of 13 different pesticide residues that were present in the compost, 4 active ingredients were detected by a multi-residue analysis on leaf samples of the plants grown with compost, and not in the control plants. None of these residues were detected in fruit samples.

It is concluded that compost derived from conventional farming may be a source of pesticide contamination of organic crops, as detected in residue analysis of the leaf mass. In some cases, this might lead to false conclusions concerning possible violation of the organic production rules by the growers.

Introduction

In the process of composting of agricultural residues most organic pollutants, like pesticides, are degraded. Kupper et al. (2008) found that about two third of all pesticides detected in the input materials showed dissipation rates higher than 50% during composting. Although many active ingredients were not detected any more after 112 days, the concentration of residues of other pesticides hardly reduced, as was particularly noticed for fungicides belonging to the group of Triazoles. Similar findings were presented by García Rández (2020). She analysed 323 potentially detectable active ingredients in 25 piles with residues of different crop types, before and after composting. In the initial mixtures, 42 active ingredients were detected, i.e., 28 fungicides, 11 insecticides y 3 herbicides. After composting, this was reduced to a total of 33 active ingredients: 24 fungicides and 9 insecticides.

La alta diversidad y actividad microbiana durante el compostaje, debido a la abundancia de sustratos en las materias primas, promueve la degradación de compuestos orgánicos xenobióticos, como pesticidas, hidrocarburos aromáticos policíclicos (HAP) y bifenilos policlorados (PCB) (Barker et al., 2002).

Contamination of crops by pesticides is especially important for organic farming, where the use of compost, also derived from conventional farming, is permitted and common practice. The organic production standards imply that no chemically synthesized products may be used for pest control or fertilization. However, the coexistence with, and proximity of, conventional farming systems in the same area may lead to certain presence of pesticides that have not been used in the crop (Bernasconi et al., 2021; Schleiffer & Speiser, 2022). Small amounts of residues may enter the organic crops, e.g. directly by ‘drift’, when neighbouring conventional crops are treated with phytosanitary products, or indirectly through residues present in input products, like organic fertilisers.

In most of the agricultural soils, including soils of organic farms, there is a persistent presence of pesticides due to agricultural practices in the past (Silva et al., 2019; Geissen et al., 2021; Riedo et al., 2021; Junta de Andalucía, 2022). In many cases, these residues remain after several years of organic horticulture. This has been demonstrated for some extremely persistent old pesticides, the use of which has ceased more than 3 decades ago, like DDT (Malusá et al., 2020), Dieldrin (Colin et al., 2022) or Lindane (COEXPHAL, unpublished report), but also for products that are still on the market and commonly used. Examples of the latter are some of the fungicides of the triazole group, e.g. flutriafol with a DT50 (time of degradation to 50% of the concentration) in soil of over 3 years (PPDB, 2023), but also for other products classified to be ‘persistent’.

Organic production reduces the presence of pesticides in agricultural soils by 70% to 90% compared to conventional agriculture, according to a study carried out by Geissen et al. (2021) with 340 soil samples from three European countries (Portugal, the Netherlands and Spain). In addition, mixtures of up to 16 residues per sample were detected in 70% of conventional soils, while only a maximum of five different pesticides were found in organic soils.

Until now, it is poorly documented how the residues present in compost may be absorbed by crops. This was the subject of the present case study, in which a commercially available compost, originating from conventional horticulture, was mixed with a basic substrate and the presence of pesticide residues in cucumber plants was monitored.

2. Material and methods

The cucumber plants (Cucumis sativa, var. Litoral®) were cultivated in an experimental greenhouse of the Research Center of CAJAMAR, Almería (Spain); the pesticide analyses were carried out by LABCOLOR, i.e. the laboratory of the association of horticultural producing companies in Almería (COEXPHAL). The experiment was repeated during three different planting cycles, with the following planting dates: 7 October 2021; 7 March 2022 and 14 October 2022.

2.1. Plant cultivation

30 days after sowing cucumber seeds in germination trays, the plantlets were transplanted into 6 liter pots, filled with only the basic substrate (control) or the substrate to which 60 g of compost was added in the first and the third trial, and 120 g in the second trial. Three groups of 6 plants per treatment were placed in a 630 m2 unheated experimental greenhouse (Figure 2), where they were managed according to the normal horticultural practices.

During the first two plant cycles, the basic substrate consisted of a homogenised soil that was taken from a part of the orchard that belongs to the experimental station, where no pesticide treatments had taken place for several years. In the third repetition, commercially available coco fibre (Fico®) was used as used as a basic substrate.

Compost was obtained from a large local recycling plant in Almería, that processes vegetable residues, mainly from the greenhouse industry in the area. Material from the same pile of compost, stored in open air at the CAJAMAR research station, was used for all three repetitions of the trial.

2.2. Pesticide treatments

The crops were managed according to Integrated Pest Management rules. This implies the use of macro-biological control agents against insect and mite pests, and the use of selective pesticides against additional pests and diseases. The treatments were carried out with pesticides that were not detected in the initial analysis of compost or soil. The products used were: Natural pyrethrum; Cimoxanilo, Sulfoxaflor, Ciazofamida, Famoxadone and Metrafenona.

2.3. Multi residue analyses

Before planting, multi-residue analyses (through gas and liquid chromatography) were carried out on the basic substrates and the compost. The compost was analysed two times: once before the start of the first trial, and once after the third trial was finished, i.e. more than 19 months after the first analysis.

From each crop, leaf and fruit samples were analysed in two occasions. The first samples were taken around the first harvest and the second samples about a month later. In the first two trials, 3 leaves were taken from each plant, from the upper, the middle and the lower level. leaves were In the third trial, only young leaves were taken, i.e. the first fully developed leaves under the growing points. From all leaves, a fragment was cut and these fragments were homogenised and processed for analysis through gas- and liquid chromatography. In all cases, the detection level of the residues was fixed at 0,01 ppm. The analyses were carried out by the laboratory of COEXPHAL (‘Labcolor’), La Mojonera, Almeria.

3. Results

3.1. Pesticide residues in substrate and compost

Despite having chosen a soil as basic substrate from part of the Research Center where no treatments had been carried out in the last years, four active ingredients were detected in this material. Two of these (Flutriafol and Fludioxonil) were also found in the compost, where they occurred in much higher concentrations. The other two, not detected in the compost, Thiabenazole and Lufenuron, are (very) persistent products which do not have a registration for use in horticulture.

Table 1 shows the results of the residue analysis of the compost, as well as of the soil that was used in the first two repetitions. No residues were detected in the coco fibre that was used as basic substrate in the third trial.

In the compost, thirteen active ingredients were detected in the first analysis, at the start of the trial (Table 1). In the second analysis of the same compost, carried out after finishing the last trial, i.e. over a year and a half later, one active ingredient had disappeared (Pyriproxyfen); two were detected in reduced concentrations; one remained the same and nine pesticides showed increased concentrations. This increase should probably be explained by the degradation (in weight and volume) of the compost itself, which was not quantified.

The active ingredients found in the compost are pesticides frequently used in horticulture in Almería and belong to the pesticides most frequently detected in organic fertilizers by the COEXPHAL laboratory (LABCOLOR, unpublished data). Therefore, the compost used can be considered representative of the area.

3.2. Residues in leaf samples

The pesticides applied to the crop during the trials were not considered. The results of the first trial (Figure 3 a and b) show that 5 pesticides were detected in the first leaf sample, around the first harvest (Figure 2a) and 4 in the second sample (Figure 3b). Two products, fluopyram and triadimenol, were only found in the plants that were grown in soil with compost. Flutriafol was detected in both treatments, although the concentration was approximately four times higher in the plants that were grown with compost.

Two pesticides, difenoconazole and fluxapyroxad), were detected in similar low concentrations in the plants grown with and without compost in the first sample. In the second sample, this was the case for spirotetramat. Since fluxapyroxad and spirotetramat were not found in the compost or the soil (Table 1), nor were they used for pest control in this crop, these detections probably are the result of contaminations.

Both products were used in other greenhouses of the experimental station, so the detection in this trial may have been caused by drifting or by remaining traces of these pesticides in the spraying equipment. Difenoconazole was detected in the compost but not in the soil (Table 1), so the origin of a low concentration in the control plants is unclear.

In the second trial, five pesticides were detected which all seem related to the concentrations in compost and soil. Fluopicolide, fluopyram and triadimenol were only detected in the plants grown with compost, Flutriafol was found in a relatively high concentration in these plants but also in a low concentration in the control plants (Figure c y d).

In the first sample, tebuconazole was present in both treatments, although in a slightly higher concentration in the plants with compost. The origin of this pesticide in the control plants is unclear, since it was not detected in the soil.

In the third trial, the basic substrate used was coco fibre, in which no pesticide residues were found previously. The first sample of this trial revealed residues of five pesticides, i.e fluopicolide, fluopyram, flutriafol and triadimenol of the plants grown with compost and no residues in the control plants (Figure 3e). All five of these products were present in the compost (Table 1). No residues were detected in the second sample in concentrations above the detection limit.

Figure 3. Concentration of pesticides (mg Kg-1) detected in cucumber leaf samples, from plants that were grown in substrate with or without compost.

- Detection limit: 0.01 mg Kg-1; Error margin in all cases: 50 %.

- No residues were detected in the second samples of the third trial.

3.3. Fruit analysis

No pesticide residues of the active ingredients that were detected in compost or soil were detected in any of the fruit samples that were analysed.

4. Discussion

Three active ingredients originating from the compost show up in foliar analyses in all three trials: triadimenol, flutriafol (both triazole fungicides) and fluopyram (a benzamide fungicide), In the second and third trial, this was also the case with fluopicolide (benzamide fungicide).

The detected concentrations were always notably higher in the first than in the second sample of each trial. Although none of these compounds was found in the fruit samples, it can be concluded that compost has been an important source of contamination by pesticides of the cultivated cucumber plants.

The residues that were found in the leaf samples were notably higher in the second trial than in the other two trials, due to the major quantity of compost that was applied (120 g per 6 l pot vs. 60 g per 6 l pot).

In the third trial, the basic substrate that was used was different from the basic substrates used in the first two trials, i.e. cocopeat instead of soil. The low concentrations of pesticides detected in the leaf samples of the third trial may thus be the consequence of the interaction of the chemical residues with the organic fibres of the cocopeat.

The registration of the two triazoles has expired in Spain in 2021, so these products are currently not in use anymore. However, when the crops were grown that were finally processed as compost, until 2021, these products still belonged to the most used pesticides, fluopicolide and fluopyram are still registered and commonly used.

The use of compost of conventional origin in organic agriculture is permitted, with the aim to value the phyto-nutritional value of organic waste according to the principles of circular economy.

This means that, as long as persistent plant protection products are allowed in conventional agriculture, small concentrations of pesticides in the organic crops must be tolerated. Usually, as in the trials presented here, these products will only be detected in foliar samples, given that contaminations in the soil may concentrate in the leaves, but not in the harvest. The residue analysis of leaf samples may even give a false indication that growers may have violated the rules concerning organic crop management.

5. References

- Bernasconi, C,, Demetrio, P,M,, Alonso, L,L,, Mac Loughlin, T,M,, Cerdá, E,, Sarandón S,J,, Marinoa, D,J,, 2021, Evidence for soil pesticide contamination of an agroecological farm from a neighboring chemical-based production system, Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment, 313: 107341. https://doi,org/10,1016/j,agee,2021,107341

- Colin, F,, Cohen, G,J,V,, Delerue, F,, Chéry, P,, Atteia, O,, 2022, Status of Dieldrin in vegetable growing soils across a peri-urban agricultural area according to an adapted sampling strategy, Environmental Pollution 295. 118666, https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2021,118666

- García Rández, A, 2020, Análisis de la presencia de plaguicidas en las mezclas iniciales y compost maduros de productores agroecológicos de la Comunidad Valenciana, El rol del compostaje en su eliminación, Escuela Politécnica Superior de Orihuela (Alicante, Spain), Master thesis, 99 pp, http://193,147,134,18/jspui/bitstream/11000/6700/1/TFM%20Garc%c3%ada%20R%c3%a1ndez%2c%20Ana,pdf

- Geissen, V,, Silva, V,, Huerta Lwanga, E,, Beriot, N,, Oostindië, K,, Bin, Z,, Pyne, E,, Busink, S,, Zomer, P,, Mol, H,, Ritsema, C,J,, 2021, Cocktails of pesticide residues in conventional and organic farming systems in Europe - Legacy of the past and turning point for the future, Environmental Pollution 278: 116827 https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2021,116827

- Junta de Andalucía, Servicio de Calidad, Promoción Agroalimentaria y Pesquera, Depto, Ecología, 2022, INFORME DE RESULTADOS DE LA TOMA DE MUESTRAS Y ANÁLISIS DE RESIDUOS PLAGUICIDAS EN LA PRODUCCIÓN ECOLÓGICA EN ANDALUCÍA EN 2021, Junta de Andalucía, 17 pp.

- Kupper, T,, Bucheli, T, D,, Brändli, R, C,, Ortelli, D,, & Edder, P, (2008), Dissipation of pesticides during composting and anaerobic digestion of source-separated organic waste at full-scale plants, Bioresource technology 99(17), 7988-7994.

- Malusá E, Tartanus M, Danelski W, Miszczak A, Szustakowska E, Kicińska J, Furmanczyk EM, 2020, Monitoring of DDT in Agricultural Soils under Organic Farming in Poland and the Risk of Crop Contamination, Environ, Manage, 66(5): 916-929, doi: 10,1007/s00267-020-01347-9, Epub 2020 Aug 19, PMID: 32815049; PMCID: PMC7591450.

- McKinnon, K,, Serikstad, G,L,, Eggen, T, 2014, Contaminants in manure – a problem for organic farming? In: RAHMANN G & AKSOY U (Eds,) Proceedings of the 4th ISOFAR Scientific Conference, ‘Building Organic Bridges’, at the Organic World Congress 2014, 13-15 Oct,, Istanbul, Turkey, p 903-904.

- PPDB, Pesticide Property Database, Univ, of Hertfordshire. https://sitem,herts,ac,uk/aeru/ppdb/en/atoz,htm

- Riedo, J,, Wettstein, F,E,, Rösch, A,, Herzog, C,, Banerjee, S,, Büchi, L,, Charles, R,, Wächter, D,, Martin-Laurant, F,, Bucheli, T,D,, Walder, F,, van der Heiden, G,A,, 2021, Widespread Occurrence of Pesticides in Organically Managed Agricultural Soils - the Ghost of a Conventional Agricultural Past? Environ, Sci, Technol, 55 (5): 2919–2928. https://doi,org/10,1021/acs,est,0c06405,

- Schleiffer, M,, Speiser, B,, 2022, Presence of pesticides in the environment, transition into organic food, and implications for quality assurance along the European organic food chain – A review, Environmental Pollution 313, 120116 https://doi,org/10,1016/j,envpol,2022,120116

- Silva, V,, Mol, H,G,J,, Zomer P,, Tienstra M,, Ritsema C,J,, Geissen V,, 2019, Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils – a hidden reality unfolded, Science of The Total Environment 653, pp 1532-1545. https://doi,org/10,1016/j,scitotenv,2018,10,441